-

Comcast-NBCU: The Winners, Losers and Unknowns

With Comcast's acquisition of NBCU finally official this morning (technically, it's not an acquisition, but rather the creation of a JV in which Comcast holds 51% and GE 49%, until GE inevitably begins unwinding its position), it's time to assess the winners, losers and unknowns from the deal, the biggest the media industry has seen in a long while. I listened to the Comcast investor call this morning with Brian Roberts, Steve Burke and Michael Angelakis and reviewed their presentation.

Here's how my list shakes out, based on current information:

Winners:

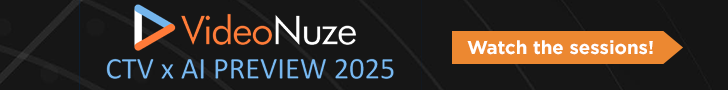

1. Comcast - the biggest winner in the deal is Comcast itself, which has pulled off the second most significant media deal of the decade (the first was its acquisition in 2002 of AT&T Broadband, which made Comcast by far the largest cable operator in the U.S.), for a relatively small amount of upfront cash. Comcast has long sought to become a major player in cable networks, but to date has been able to assemble an interesting, but mostly second tier group of networks (only one, E! has distribution to more than 90 million U.S. homes).

The deal moves Comcast into the elite group of top 5 cable channel owners, alongside Disney, Viacom, Time Warner and News Corp, with pro-forma 2010 annual revenues of $18.2 billion and operating cash flow of $3 billion. It also provides Comcast with a huge hedge on its traditional cable/broadband/voice businesses, as the JV, on a pro-forma basis would be 35% of Comcast's overall 2010 revenue of $52.1 billion, though importantly only 18% of its cash flow of $16.5 billion. On the investor call, Roberts emphasized that the deal should not be seen as the company diminishing its enthusiasm for the traditional cable business, but given the downward recent trends in fundamentals (vividly shown in slides from my "Comcast's Digital Transformation Continues" post 3 weeks ago), the conclusion that Comcast will be relying on its content business for future growth is inescapable.

2. Cable networks' paid business model/TV Everywhere - With Comcast's executives' platitudes about cable networks being "the best part of the media business," the fact that cable networks will contribute 80%+ of the JV's cash flow and the ongoing travails of the ad-supported broadcast TV business, the deal puts an exclamation mark on the primacy of the dual-revenue stream cable network model and Comcast's commitment to defending it (see "The Cable Industry Closes Ranks" for more on this.)

The deal can also be seen as cementing the paid business model for online access to cable networks' programs. Comcast is committed to having online distribution of TV programs emulate the cable model, where access is only given to those consumers who pay for a multichannel subscription service. Much as they may resist acknowledging it, Hollywood and the larger creative community must see Comcast as doing them a huge service by preserving the consumer-paid model, helping the video industry avoid the financial fate of newspapers, broadcasters and music. To be sure, some consumers will cut the cord and be satisfied with what they can get for free online, however it is unlikely to be a large number any time soon. As for aspiring over-the-top providers, they'll need to look outside the cable network ecosystem to generate competitive advantage.

3. Jeff Zucker - The current head of NBCU will migrate into the role of CEO of the JV, greatly expanding his portfolio and influence. Zucker has fought the good fight to preserve the NBC network's status, rotating in new creative heads, shifting Leno to primetime, backing Hulu, etc, but the reality, as he pointed out earlier this year, is that NBCU in his mind has long since become a cable programming company. I've been a Zucker fan since seeing him speak at NATPE in '08 when he laid out a sober assessment of the broadcast business. Through solid acquisitions and execution, Zucker has proved himself to be far more than the wonderboy of "Today" - he's going to fit in well at Comcast and be a great addition to its executive team.

Losers:

1. NBC broadcast network and the JV's 10 owned and operated stations - While Comcast executives said they "don't anticipate any need or desire to divest any businesses" and "take seriously their responsibility" to the iconic NBC brand, the reality is that with the broadcast business contributing just 10% of the JV's pro-forma annual cash flow, the network, and especially the stations, are not just in the back seat of the JV, they're in the third row. Though broadcast contributes 38% of the JV's pro-forma revenue and the deal is being struck near the bottom of the advertising recession, it's hard to see things improving much. Exceptions are the sports division (more on that below), the TV production arm and possibly the news division. The only thing saving the stations is retrans and Comcast's need to appease regulators to get the deal done and keep the regulators at bay thereafter.

2. Other cable operators, telcos and satellite operators - It's never good news when one of your main competitors owns the rights to a good chunk of the key ingredients in your product, yet that's the reality for all other cable operators, telcos and satellite operators. Sure Comcast must be disciplined about throwing its weight around too much, but if these distributors cried when NBCU (and other big network owners) forced bundling and drove fee increases, they haven't seen anything until Comcast runs the renewal processes. With 6 channels having 90+ million homes under agreement plus many others in the JV's portfolio, Comcast is in a very strong negotiating position. As the world moves online, the threat that Comcast eventually says to hell with other distributors and goes over the top itself (a scenario I described here), other distributors have even bigger problems ahead.

3. GE - Yes GE gets about $15 billion in cash and a graceful exit from NBCU, but 20 years since incongruously acquiring NBC, the question burns even brighter, what was GE doing in the entertainment business in the first place? Hasta la vista GE, time to focus on manufacturing turbines and unraveling the woes at GE Capital.

Unknowns:

1. Do content and distribution go together any better this time around - With the disastrous results of AOL-Time Warner still fresh in the mind, it's fair to ask whether vertical integration will work any better this time around. Sensitive to the issue and no doubt anticipating questions on it, Roberts said on the call that this is "a different time and a different deal" and, pointing to News Corp-DirecTV, noted that sometimes vertical integration does work. In addition, he highlighted that the deal's financials are not predicated on achieving any elusive synergies. Still, aside from the obvious benefits of getting bigger in cable networks, the primary reasons cited for Comcast pursuing the deal still have synergy at their core: a slide that clearly says that "Distribution Benefits Content" and "Content Benefits Distribution." As always there are plenty of opportunities to pursue in theory; the challenge is executing on them given the rampant conflicts and turf battles that inevitably ensue.

2. Hulu's future - the online aggregator was literally not mentioned once in the Comcast presentation and its logo only appears on just one of the 36 slides in the deck, yet its presence is hard to underestimate. Hulu is the embodiment of the free, ad-supported premium video model that Comcast is so fiercely committed to combating. So how does it fare when one of its controlling partners soon will be Comcast? In response to a question, Steve Burke said he sees "broadcast content going to Hulu" and that "Hulu and TV Everywhere are complementary products." He also tersely dismissed the much-rumored idea of a Hulu subscription offering. It's impossible to know what becomes of Hulu, but with such divergent interests among the owners, it wouldn't surprise me if Hulu is unwound at some point post closing.

3. ESPN's role - With the JV's NBC Sports assets, plus Comcast's Versus, regional sports networks and Golf Channel, the new JV is primed to play a bigger role in national sports. While Fox Sports and TNT have skirmished for high-profile rights deals with ESPN, the new JV has a much stronger hand to play. It's fair to wonder whether Comcast, which likely sends Disney a check for $70-80 million each month to carry ESPN to its 24 million subscribers, won't at some point say, "hey we can do some of this ourselves" and move to become a bona fide ESPN competitor. In fact, ESPN figures into a far larger Comcast vs. Disney story line in the media industry going forward. The two companies are incredibly dependent on each other, and yet are poised to become even tougher rivals. Expect to hear much more about this one.

4. Consumers - last but not least, what does the deal mean for consumers? Likely very little initially, but over time almost certainly an acceleration of digitally-delivered on-demand premium content - but at a price. Comcast has the best delivery infrastructure, with the JV, soon premier content assets and a persistent, if sometimes incomplete (as with VOD, for example) commitment to shape the digital future. I expect that will mean lots of experimentation with windows, multiplatform distribution and co-promotion across brands. Washington will scrutinize the deal thoroughly, but with continued public service assurances from Comcast, will eventually bless it. Then it will be vigilant for anything that smacks of anti-competitiveness. Consumers should buckle up, the next stage of their media experience is about to begin.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Aggregators, Broadcasters, Cable Networks, Cable TV Operators, Deals & Financings

Topics: Comcast, GE, Hulu, NBCU

-

Flip's New FlipShare TV Will Likely Flop

With today's unveiling of FlipShare TV, the folks behind the enormously popular Flip video cameras are betting that users want to watch their personal videos on their big-screen TVs and also be able to share their videos with friends and family. I think Flip is 100% right about users' interests, but the company's proprietary and expensive FlipShare TV approach is off the mark, and will likely flop. Flip would have had more success by partnering with key players in the video ecosystem, benefiting from both their momentum and numerous co-branding opportunities, while also avoiding costs incurred to develop and market FlipShare TV.

FlipShare TV consists of 3 items: a small base station that connects to the TV via HDMI or composite cables; a USB stick that has a proprietary 801.11n wireless interface so that videos on the computer can be

streamed to the base station (and hence viewed on the TV); and a remote control. Included FlipShare software lets users create "Flip Channels" which are groups of videos. FlipShare TV costs $150, a not-insignificant amount given Flip video cameras themselves have MSRPs of $150-$230, but can often be found for far less via online deals (I bought my daughter one for $60 recently).

streamed to the base station (and hence viewed on the TV); and a remote control. Included FlipShare software lets users create "Flip Channels" which are groups of videos. FlipShare TV costs $150, a not-insignificant amount given Flip video cameras themselves have MSRPs of $150-$230, but can often be found for far less via online deals (I bought my daughter one for $60 recently).The problem with FlipShare TV is that it takes a grounds-up approach to solving problems that could have been solved instead through smart partnerships and relatively straightforward integrations. Flip should have created a free or nearly free TV viewing and sharing feature that would have helped distinguish Flip's video cameras from the extensive list of competitive products hitting the market rather than creating a whole new product.

FlipShare TV's core proposition is of course making users' videos viewable on their TVs. The most obvious approach to doing so would have been to just partner with convergence product companies who are jockeying for position in the living room. The first partner in this space would have been Roku, which just released open APIs to support its Channel Store. I anticipate many other convergence players (e.g. Blu-ray, Internet TVs, gaming consoles, etc.) will similarly offer APIs to inexpensively broaden their offerings. As this occurs, Flip could have piggybacked on these devices. Netflix is doing this pre-emptively in the absence of APIs through brute force integrations; if it had wanted to, Cisco, Flip's parent, could have afforded to do so as well.

FlipShare TV's other value proposition of sharing could have been addressed through partnerships with companies such as Motionbox, iMemories and Pixorial which are targeting the family's "Chief Memory Officer." Motionbox is in fact already on Roku's Channel Store, which would have meant one less Flip integration. These companies are agnostic about how users capture their video, but all would have likely been eager to partner with well-known Flip to add to their brand awareness and their own value propositions.

YouTube would have been another obvious partner to enhance sharing. Granted YouTube lacks a strategy for getting onto the TV, but its online reach is unparalleled and features that would have enhanced YouTube uploading which is already prevalent among Flip users could have been valuable.

A major kink in FlipShare TV's sharing approach is that the sharee (e.g. grandma and grandpa) themselves also have to buy a FlipShare TV so they have the base station to connect to their TVs. Pew recently estimated 30% of seniors now have broadband Internet access (a number that's likely far higher for grandparents who have tech-forward, Flip-buying kids and grandkids). My guess is that sharing videos via a private YouTube channel would have been adequate for most of them if faced with the alternative of spending $150 for a proprietary setup.

All of these potential opportunities somehow didn't register with the Flip team. Their focus on a proprietary approach seems so complete that they didn't even choose to leverage existing wireless home networks among their target audience (Pew estimates home wireless penetration at about 40% for all broadband homes; it's likely double that or more in homes where a Flip camera's been purchased). Instead, additional cost was added to FlipShare TV system with the proprietary USB wireless stick.

I could be way off base on this and underestimating consumers' willingness to buy proprietary hardware, but I suspect I'm not. FlipShare TV's underlying concept of viewing on TVs and sharing is right on, but my guess is that its execution will yield little success. The lesson here: when partnerships are readily available, capitalize on them.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Devices

Topics: Flip, FlipShare TV, iMemories, Motionbox, Pixorial, Roku, YouTube

-

LiveRail Lands PBS for Video Ad Management

LiveRail, a video ad management company, notched a high-profile customer win yesterday, announcing that PBS will use the company's platform to deliver sponsor messages on its recently launched PBS.org video

portal and its 356 member stations' online video outlets. PBS is making an aggressive play in online video and has gained many positive reviews of its portal, which provides access to all of its full-length programs and more.

portal and its 356 member stations' online video outlets. PBS is making an aggressive play in online video and has gained many positive reviews of its portal, which provides access to all of its full-length programs and more.LiveRail's CEO Mark Trefgarne and EVP Nic Pantucci explained to me yesterday that they're building a suite of tools that equally addresses all 3 constituencies in the ecosystem - publishers, advertisers and ad networks. The company is focused on the following 3 differentiators to separate itself in a pretty crowded video ad management space:

- Enhanced optimization that allows simultaneous querying of multiple ad sources to determine the highest effective CPM ad to serve (Mark and Nic said that using LiveRail one customer saw an jump in their ad fill rate from 40% to 90%)

- More flexibility in distributing and customizing ads to affiliates, based on a sub-account authorization system (this was particularly valuable for PBS with its hundreds of member stations and multitude of sponsor messages)

- Integration with the broadest set of 3rd party ad networks, using an extensive series of open APIs (this helps with time to market and reducing cost of integrations)

Of course, the real way to validate these benefits and compare LiveRail to others is by getting hands-on and trying the platform out. I've offered similar advice in the past when assessing the variety of online video platforms.

LiveRail was started in 2007, has 15 employees and has raised $1.5 million to date, though it sounds like there may be financing news upcoming. The video ad management space includes others like FreeWheel, Adap.tv, Tremor Media (with its Acudeo product), Auditude and others.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Advertising, Technology

-

The Opportunity for Paid Streaming of TV Shows Seems Narrow

A report this morning by Peter Kafka saying that YouTube is in discussions with TV networks to allow it to stream programs, commercial-free, for $1.99 apiece suggests to me that TV networks are in a tight place when it comes to trying to charge for streaming TV episodes.

The $1.99 figure happens to be the same amount currently charged by iTunes and Amazon (for example) to download and own an episode. If there's no material difference in value, then it's pretty straightforward to conclude that such a YouTube initiative would likely fail. Consumers will quickly ask - why would I rent

something one time for $1.99 when I can own it for the same price? The folks at YouTube must surely understand this too, and therefore be angling for something that would provide their rentals differentiated value vs. the current download-to-own models.

something one time for $1.99 when I can own it for the same price? The folks at YouTube must surely understand this too, and therefore be angling for something that would provide their rentals differentiated value vs. the current download-to-own models.The $1.99 figure was set several years ago, likely pitched somewhat arbitrarily by Apple to TV networks to govern the original iTunes download deals. Apple no doubt wanted the price point to be low enough to spur download volume, which would in turn drive sales of video-enabled iPods, yet different enough from the $.99 it was charging for song downloads. At least some of the TV networks likely thought this price point was too low from the start (a position underscored when NBC temporarily pulled its programs off iTunes 2 years ago in order to obtain more pricing flexibility), but acquiesced because of their desire to experiment with digital delivery and their lust to get into business with Steve Jobs.

Now however, the $1.99 price point is pretty well cemented in consumers' minds. Because streaming inherently provides less value than a download (lower video quality, requirement to be connected, etc.), in order for paid streaming to succeed, an episode surely needs to be priced lower than $1.99. But because Hulu and the networks themselves provide programs for free, streaming access to many TV episodes is already a reality. Further, I suspect most TV executives would be loathe to charge $.99 or less for a streaming TV program, as it sets up the consumer perception (albeit an incorrect apples to oranges one) that a TV episode is worth less than a music download.

Given these circumstances, this suggests that pricing for streaming TV episodes likely needs to fall somewhere in the $1-$2 range to have any shot of success at all. Even in this range, I'm skeptical that standalone paid-for streaming episodes will catch on. Few consumers download programs in sufficiently high volume to have the potentially lower differential streaming pricing save them much money. In short, they'll be inclined to keep on buying and downloading, even if they perceive they won't watch the show more than once or twice. The real problem is that the download price was originally set too low. If it were higher - even $2.99 or $3.99 per episode - that would have created more headroom to stake out a value proposition for streaming.

Yet another issue is that TV Everywhere is going to provide streaming of many TV shows anyway. Granted you'll have to be a paying video subscriber, but if TV Everywhere marketers are clever, they'll be able to create the perception that the streaming episodes are "free" causing even more pressure on standalone paid-for streaming. Networks would likely be better off trying to figure out how to get a piece of the TV Everywhere action.

In general I'm a fan of experimentation, but in this case I'm hard-pressed to see how TV program streaming for a fee will succeed.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Aggregators, Broadcasters

-

Parsing Hulu's 856 Million Streams Yields Valuable Insights

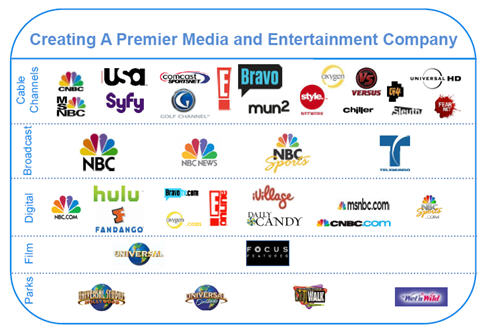

Just before the Thanksgiving buzzer went off for many last Wednesday, comScore released its October 2009 Video Metrix data under the banner headline "Hulu Delivers Record 856 Million U.S. Video Views in October During Height of Fall TV Season." Hulu's 856 million views (which are 47% higher than its September total of 583 million) are indeed eye-grabbing. When viewed in the context of Hulu's performance to date, as tracked by comScore since May, 2008 shortly after the site's launch, it's possible to glean a number of valuable insights.

Below is a chart with comScore's data for Hulu's total monthly video views and unique visitors since May '08. The blue bars would make any online content CEO swoon; in the 18 months since it launched, Hulu has increased its monthly views nearly 10-fold, from 88.2 million in May '08 to this past October's 856 million.

Two clear viewership spikes are noticeable - from July '08 to Oct '08 there was a 97% increase in views (from 119.3 million to 235 million) and from July '09 to Oct '09 there was an 87% increase (from 457 million to 856 million). It should be noted that the Nov '08 total of 226.5 million was down nearly 4% vs. Oct '08, potentially foreshadowing a decrease to come in Nov '09 as well. Other than this dip, there has been only 1 other sequential monthly drop in Hulu's views, a 6% drop from April '09 to June '09. Taken together, Hulu's steady, yet dramatic increase in viewership is remarkable.

On the other hand, I believe the red line in the chart, showing unique monthly visitors, raises some concerns. You'll notice that after a solid 20% jump in uniques from Feb '09 (34.7 million) to March '09 (41.6 million), unique visitors have stayed in a fairly level range through Oct '09 (42.5 million), with uniques actually below the 40 million mark for Jun-Sept. This contributes to a theory I've been developing about Hulu for some time now: in its current configuration, I think it's quite possible that Hulu has saturated the market for its content and user experience. This isn't a hard-and-fast conclusion, but it's worth noting that even with the addition of the ABC programs, Hulu's uniques are scarcely better than they were 6 months ago. Unless the unique number jumps in the coming months (and I doubt it will), Hulu will have to meaningfully enhance its value proposition to grow its audience (can you say "Hulu-to-the-TV-via-Xbox/Roku/Apple TV/etc?").

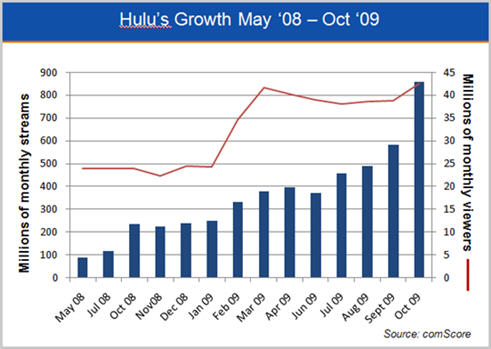

As the blue bars in the chart below show, usage of Hulu by its users is growing nicely. According to comScore, the average Hulu viewer viewed 20.1 videos on the site in October, up 33% from September's 15.1 videos, and nearly double July's 10.1 videos. In October Hulu drove almost double the number of videos/viewer as the Microsoft (11.1 videos) and Viacom (10.3 videos) sites, though it still lags the Google sites, which are primarily YouTube (83.5 videos) by an enormous margin. As I've said many times, YouTube is the month-in-and-month-out 800 pound gorilla of the online video market.

As shown by the red line in the chart, the 120 total minutes viewed per Hulu viewer is roughly even with Nov '08. However, it's possible that comScore was measuring this differently a year ago, as Hulu's minutes per viewer drop dramatically and oddly, from Nov '08 to Mar 09 (58 minutes). Since that time though Hulu's minutes per viewer have steadily increased.

That said, as the yellow line shows, the minutes watched per video have stayed remarkably constant, hovering in a very narrow range around 6 minutes since Mar '09. Hulu's users are spending more time on the site watching more total videos, but it seems they watch a very consistent mix of short clips and longer programs each month. In fact, while Hulu is commonly thought of as a site for full-length TV programs, only 1 of its top 10 most popular videos of all time is a full program and not a short clip, and only 6 out of its top 20 videos are full programs (though the mix may be changing as this month 8 out of the top 10 and 16 out of the top 20 most popular are full programs). To the extent that Hulu viewers stick with a program to its end, the current month's usage would suggest that minutes watched per video is poised to increase, along with it revenue per user session, which is an important barometer of the site's success.

With its exclusive access to 3 of the 4 broadcast networks' hit programs, Hulu has significant competitive advantages, which it has further capitalized on with its superb user experience. Despite positive and encouraging reports about its ad sales efforts, Hulu still has a long way to go to prove it can monetize its audience as effectively as its parent companies can do with programs viewed on-air. As a result speculation about a Hulu subscription service (which I consider inevitable) will continue to loom.

Other variables affecting Hulu's future also swirl: what will Comcast do if/when it acquires NBCU and therefore becomes a Hulu owner? What happens to Fox's programs on Hulu should Rupert Murdoch expand his focus beyond his newspapers' online content going premium? What if Disney decides to launch its own subscription services? What if Google or Microsoft or Netflix (or someone else) decides to open their wallet and make a bigger play in premium online video?

Hulu is still a relatively young site and the insights above are not fully conclusive, especially because they're based on 3rd party data. Hulu has clearly built a solid brand and user experience. Its monthly performance is well worth following.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Aggregators

-

Giving Thanks

As Thanksgiving approaches, it's time to pause and say a few important thank yous. First, thank you to VideoNuze's readers, the executives who are on the front line of the broadband and mobile video revolution. You are inundated each day with announcements and other news sources competing for your attention, so I appreciate you taking time to read VideoNuze, comment on it, pass it along to colleagues and provide me with ideas for further posts.

When I started VideoNuze 2+ years ago, my goal was for it to become the main online source for busy industry executives looking for daily analysis that goes beyond the headlines often found elsewhere. I wanted to provide fact-driven, well-reasoned arguments for my positions, and when being critical, explain why constructively, without being snarky. VideoNuze is all about executive-level, clear-headed analysis plus aggregating the most important industry news from other sources. Your feedback that VideoNuze has indeed become an authoritative voice for understanding key industry initiatives has been very gratifying.

A big thanks also to VideoNuze's loyal sponsors, whose support makes VideoNuze possible. Current sponsors Akamai, Brightcove, Microsoft Silverlight, Twistage, ActiveVideo Networks, Digitalsmiths, ExtendMedia, Jambo Media and Visible Measures are all making key contributions to the broadband video ecosystem, and I encourage you to check them out.

Back in the summer of '07, when I originally pitched the idea of VideoNuze to a small group of broadband video companies, I relied on an executive summary and assumptions about audience growth. Eight companies came on board as charter sponsors, and as VideoNuze's email distribution and site traffic have grown, another 40+ companies have become sponsors. These companies gain strong branding and lead generation at an extremely cost-effective CPM (if you'd like to learn more about sponsoring, please contact me).

Thanks also to the many industry executives who have taken time this year to brief me on their companies' activities and also to help educate me about the industry. I learn a ton from these conversations, and they help me road-test and synthesize different ideas I'm developing. Often there are hard-working PR professionals facilitating these briefings, being persistent about getting the calls set up. I appreciate how really good PR people understand VideoNuze's editorial focus and know when their clients' news is a good match.

In 2009, VideoNuze stepped up its event calendar, hosting 2 VideoSchmooze events in NYC and a breakfast at the CTAM Summit in Denver. I've received lots of positive feedback on these as being targeted, cost-effective and high-quality networking/educational opportunities. Thanks to the hundreds of you that attended. There's lots more planned next year, which you'll be hearing about soon.

In 2009 I also spoke at more than a dozen private company meetings - at executive off-sites, all-hands meetings, customer outings and sales/marketing strategy sessions. I'm continually revising a presentation that I share which explains the broadband industry's key trends, data and upcoming technology/product shifts. These meetings are very interactive and they've been a great opportunity for me to get really deep with key players in the market (off the record) about what they're doing and what's ahead. If I can add value to a meeting you're planning, please let me know.

Last but not least, thanks to 2 partners who help distribute the daily VideoNuze email, the National Association of Television Program Executives and The Diffusion Group. Each is doing outstanding work in the broadband video space as well, and I continue to be involved in their activities. And thanks to my weekly VideoNuze Report partner Daisy Whitney, with whom I've cranked out 40+ podcasts this year.

If you're on the road this weekend for Thanksgiving, travel safely and enjoy. VideoNuze will be back on Monday for the home stretch of 2009.

Categories: Miscellaneous

Topics: VideoNuze

-

Oprah's New Channel Reinforces Value of Paid Distribution Model

Oprah Winfrey's decision last week to voluntarily wrap up her long-running talk show captured the biggest headlines, but a more subtle takeaway message should also be noted: even in the broadband age where content providers can connect directly to their audiences, there's still enormous value in working through distributors who are willing to pay a guaranteed monthly fee to carry a 24/7 linear channel. In this case the channel is new Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN), which is a 50-50 joint venture with Discovery Communications and will be Oprah's main business focus.

OWN is actually taking over the 70 million home (U.S.) carriage that Discovery established for its digital channel Discovery Health Channel which didn't generate much ratings success. This allows OWN to count on an established revenue stream from its distributors before a single program has been put on air or a single ad has been sold. As a result, a portion of the new venture's financial risk is mitigated from the start. Of course there will still be huge pressure on OWN to create programs that have sustainable audience appeal (the bread and butter of all networks, cable or broadcast), but the cushion of those monthly distributor payments cannot be underestimated.

I've said for a long time that the fundamental differentiating aspect of broadband video is that it is the first open video delivery platform. By open I mean that content providers are able to reach their intended audiences without requiring deals with any third party cable operator, satellite operator, telco, cable network, broadcast network, local broadcast TV station, etc. If you're a producer, that's incredibly liberating: just put your video up on a server and online audiences have immediate access to it. YouTube's 10 billion+ monthly streams, many of which are user-generated, attest to how powerful a concept open video delivery is.

Of course the problem is that just because you can produce video and make it available, doesn't mean it has any economic value to an advertiser or to a distributor. By definition distributors only seek to take on products that they believe have value in the retail marketplace. In cable's early days, operators were desperate to differentiate themselves as more than retransmitters of broadcast stations and were willing to take on channels with untested and often quizzical formats: 24 hour news (CNN), music videos (MTV) and low-popularity sports (ESPN), among others. Over time the fees these channels and others command have grown significantly, helping fuel their programming budgets and in turn their audience popularity.

But as anyone who has more recently tried pitching a new cable network to a cable, satellite or telco operator knows, the standards for getting distribution have become insanely high. It's not just that these cable/satellite/telco operators need to keep their costs down because they have limited ability to raise their monthly rates, it's also that they recognize very few new channels can generate bona fide new value in their lineups. This is part of why the few recent channel success are sports-driven startups like the NFL Network or regional sports outlets like the Big Ten Network.

A comparable paid distribution model has not yet developed for broadband video. For a time I believed that sites like Hulu, Joost and Veoh might be able to develop such a model given the amount of capital that each had raised. Only Hulu now has the potential to do so, though there's no indication as yet that it intends to. Absent a paid distribution model, the vast majority of broadband-only video producers are reliant on advertising, just like broadcast TV networks. Some broadband producers are proving that an ad-only model works, yet there's no question a viable paid distribution model would be a tremendous boost for the industry.

Watching Revision3's Tekzilla on TV the other night via Roku, I was reminded that until broadband video is widely available on TVs it will remain hard for any new paid distribution model to take root. That's because consumers will require a comparable living room viewing experience before many of them show a willingness to pay. The good news is that this experience is coming, as millions of TVs will soon have broadband access, either on their own or through a connected device (e.g. Roku, Xbox, Apple TV, etc.). Until then though, the paid distribution model will only be available to Oprah and others with gold-plated appeal.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Cable Networks, Cable TV Operators, Indie Video, Satellite, Telcos

Topics: Discovery, Oprah Winfrey Network

-

Roku's Channel Store Launches, Positioning Player as Open Platform

Roku is launching its Channel Store today with 10 free channels, bidding to become the must-have broadband-to-the-TV video player in an increasingly crowded space. With the Channel Store Roku is releasing a free software developer kit (SDK) that further content partners can use to create an application to run on Roku players. Up until now Roku has selected its content partners (Netflix, Amazon VOD and MLB.TV), but the SDK helps Roku re-position itself as an open platform, available for all legal and non-adult content providers. Existing Roku players will get a software upgrade to enable the Channel Store, while new players receive the software upon initial install.

I got a sneak peak at the Channel Store over the weekend using the new Roku HD-XR player which itself was recently released. The 10 channels include Pandora, Facebook Photos, Revision3, Mediafly, TWiT, blip.tv, Flickr, Frame Channel, Motionbox and MobileTribe. The Content Store is a new icon on the Roku home screen, alongside the 3 existing partners. After selecting it, the 10 new channels' icons are visible along with their respective shows and their episodes.

The video quality is terrific; as with prior Netflix movies I've watched there's no buffering, the audio and video are in synch, it's possible to pause, fast-forward and rewind and come back later and resume at the same spot. The only issue I had was that the start-up time for new shows was very slow, sometimes taking up to 5 minutes while the screen said "retrieving...." I'm chalking this up to using the Channel Store pre-release, as Netflix movies I also retrieved over the weekend loaded quickly as they always do.

One other minor annoyance was that to watch Revision3 shows I had to first create an account at Revision3. Only after doing so and linking my Roku to that account was I able to start watching. I guess I understand that Revision3 wants to know who's watching via Roku, but the hurdle will suppress sampling of its shows when users are in channel surfing mode. Plus, online I'm able to watch Revision3 shows like Tekzilla without an account. I'd like to see the Roku process streamlined to emulate online.

Roku's spokesman Brian Jaquet explained to me that these 10 channels are just the start. Just as Apple has done with the App Store, Roku imagines letting a thousand flowers bloom, with an expanding variety of popular content helping drive sales of Roku players. The company has set up an affiliate program so that content partners that help sell players get a commission. It is also experimenting with different internal discounts that incent partners to sell players.

As I wrote in back in August, I continue to be bullish about Roku's prospects. Though I'm generally not a fan of new special purpose boxes, Roku has a few key things going for it that make it appealing to all-important mainstream buyers: piggybacking on existing well-known brands (e.g. Netflix, Amazon, MLB, Pandora, Facebook, etc.) to drive awareness, a low price-point that neutralizes much of the buyer's purchase risk, and a dead simple process of connecting and getting started. While boxee, for example, has for now appealed mainly to early adopters, Roku has from day 1 been positioned as a mainstream product (note boxee plans to launch its own box shortly along with its beta version). The Channel Store will only help broaden Roku's appeal. If Roku could clinch a promotional deal with Netflix, that would be a killer this holiday season, especially as a stocking stuffer.

Nonetheless, I still don't expect Roku or any of the other Internet-connected devices to incite a wave of cord-cutting any time soon. These are still "fill-in-the-gaps" kinds of value propositions; access to linear broadcast and cable programming is required for any of them to be considered bona fide substitutes to cable/satellite/telco. The risk to the incumbent providers is that new devices continue getting stronger, making them appealing as "good enough" alternatives to some portion of viewers. The Channel Store gives Roku that potential, as well as a leg up on the myriad other connected devices currently hitting the market. It will be worth watching over time.

What do you think? Post a comment now.

Categories: Devices