TV’s Ad Apocalypse Is Getting Closer

Disney’s decision to build its own streaming service is smart. It’s also the latest sign that the traditional cable bundle is doomed.

Disney announced on Tuesday that it will stop selling content to Netflix by 2019 and will instead launch two streaming services—one with sports content from ESPN (which it owns) and another for movies. It is a dramatic announcement with far-reaching implications for the future of television and, pulling back the lens even farther, the U.S. tech and media landscape.

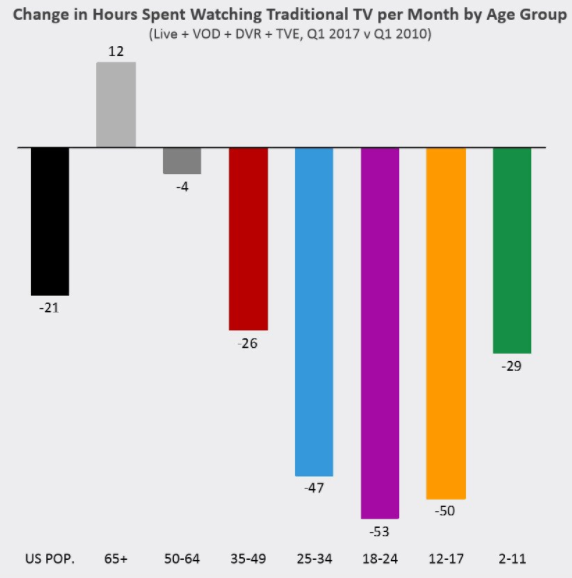

Before getting to the future, let’s start with the present of television. Pay TV—that is, the bundle of channels one can buy from Comcast or DirecTV—is in a ratings free fall among all viewers born since the Nixon administration. Since 2010, the time that Americans under 35 have spent watching television has declined by about 50 percent, according to Matthew Ball, the head of strategy at Amazon Studios.

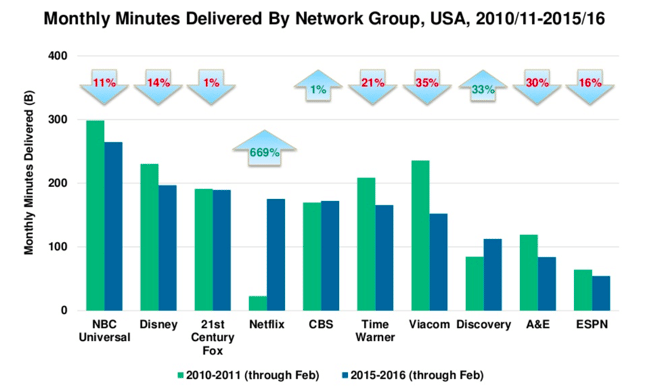

As a result, Disney’s cable-television business, once the crown jewel of the company, is now weighing down its stock. Where are its viewers going? Many have decamped for streaming services like Netflix, where the number of hours of video entertainment consumed has grown by about 700 percent in the same time.

Kleiner Perkins

This has created a business crisis for entertainment companies like Disney. Old Disney’s television strategy was: Focus on making great content and then sell it to distribution companies, like Comcast and DirecTV. This worked brilliantly when practically the entire country subscribed to the same television product. For example, when Disney sold its goods to Comcast, it stimulated demand for the cable bundle, which meant more people had access to ESPN, which meant ESPN’s advertising revenues soared, which meant Disney profited. Thanks to virtuous cycle of bundling, separating content and distribution used to be the obvious play for Disney.

But New Disney is looking for a fresh play. Now that young households are cutting the cord, it wants to own both content and distribution. Netflix once famously said that it wanted to be HBO before HBO could be Netflix; that is, to become a great content company before HBO could become a technology company. With this week’s announcement, Disney is declaring that it wants to rival Netflix, as a streaming competitor, before Netflix can rival Disney, as a prodigious content-owner and rights-holder.

This move may be necessary, but it’s awfully risky. Disney is the envy of the entertainment industry by virtue of its catalogue, which includes Star Wars, Marvel, Pixar, and a legendary animated-films portfolio. Its ability to re-merchandize its most popular content, with amusement parks, toys, and sequels, is unparalleled. But it is not a technology company. There aren't many great examples of legacy media empires successfully transitioning to the digital age without a few disasters along the way, or at least a long period of readjustment. Just look at American newspapers, or the music labels at the beginning of the 2000s.

This announcement is only days old, but it’s not too early to anticipate the furthest-reaching implications of “Disneyflix” on the future of media and technology.

Disney’s streaming products will debut in a crowded marketplace. Netflix has 50 million domestic subscribers. Hulu has 12 million. Tens of millions more subscribe to Amazon Video, as part of their Prime subscriptions. Disneyflix will start from way behind, and it will have to offer something compelling—on price, quality, or convenience—to get millions of people to pay for yet another TV thing. What might its pitch include?

One seemingly banal prediction would be commercial-free access to its incredible catalogue of films. Or, at least, very few commercials for non-sports content. (Sports rights are expensive, and live sports often has so many breaks that it would be weird if there's weren't commercial interstitials. ) This seems like a pretty modest offering. After all, Netflix and Amazon already offer an ad-free experience.

But play this out: Imagine that the Disney bundle is seen as a modest success, as is possible given the strength of its current catalogue. Other media companies might follow suit, and, before long, there might be an NBCUniversal bundle, a 21st Century Fox bundle, and a Time Warner bundle. All of these streaming services would be jostling for America’s limited entertainment budget and limited TV-viewing time. They would all feel the pressure to lure subscribers with the promise of fewer ads, or a commercial-free experience.

Where would this leave U.S. TV advertising, which companies spend $40 billion a year on? Very endangered. After all, each ad-free streaming product is yet another reason to dump the ad-rich cable bundle.

“All right,” one might think. “So more and more Americans will see fewer and fewer commercials. This is a really boring hypothetical.”

Except that $40 billion of advertising won’t just disappear. Ad dollars never do. The share of U.S. GDP that goes to advertising has been almost thermostatically constant, hovering between 1 and 1.5 percent for the last 90 years.

Spending on Advertising in the U.S. as a Percentage of GDP

As a large chunk of television moves toward an ad-light experience, tens of billions of dollars that used to fit in the nooks between Chuck Lorre comedies and Law & Order reruns will look for new homes. This isn’t a radical extrapolation; it’s already happening inside of pay TV. In Disney’s last quarter, subscription fees for its cable networks grew slightly while ad revenue declined 7 percent. CBS, the most-watched broadcast channel, is already "evolving away from the primary reliance on advertising revenues,” according to a recent report from the media research company MoffettNathanson.

Where will the ad money go? To the Internet, naturally. (The other options—like print, podcasts, and radio—don’t seem like they’re poised to absorb billions of dollars in new advertising, although perhaps video games and augmented/virtual reality platforms will benefit.) And when it comes to digital advertising, there are really two companies that stand apart from the rest: Google and Facebook.

Google and Facebook account for more than half of domestic mobile advertising. What’s more, they’re also growing faster than the rest of the market combined, and they’re both trying to build television-like products to keep users from leaving their ad-rich ecosystems. Thus, wise strategy adjustments from Disney and other TV corporations may free up billions of dollars of revenue that several other media and technology companies will clamor for, but which Facebook and Google are uniquely poised to capture.

This won’t be a sudden shift, and nothing in marketing is inevitable. If GEICO’s commercial business doesn’t want to pull away from TV, no one can make them. But television seems to be inexorably moving to a model where the cable bundle will continue to shrink among non-seniors, ad-light streaming products will grow in both total number and total subscribers, and TV advertising will be evermore concentrated in sports while much of the rest lurches toward the Internet. As I’ve written before, Netflix’s extraordinary success is the best thing that could have ever happened to digital advertising. And Google and Facebook, in particular, could not have designed a more effective corporate assassin.