There’s no bigger Internet service provider in the United States than Comcast, and perhaps none is more controversial.

Comcast has struggled to win the hearts of its TV and Internet subscribers for years, regularly faring poorly in customer satisfaction surveys. Yet, somehow it has managed to become an even bigger lightning rod over the first half of this year.

The latest controversies involve a crucial part of the Internet that many Americans are likely unfamiliar with: the interconnections between last-mile Internet service providers like Comcast and the companies that distribute traffic from content providers such as Netflix.

These connections, known as peering and transit, are under increased scrutiny because of high-profile money disputes between Netflix and ISPs including Comcast. Comcast’s proposed acquisition of Time Warner Cable (TWC) complicates matters, too. Netflix and other critics say this merger will give Comcast additional power to demand payment from companies that want to offer services to Comcast subscribers without suffering congestion.

Comcast’s dispute with Netflix—which ended with Netflix paying Comcast for a direct connection to its network—put a spotlight on a fact some of Comcast’s biggest critics probably would rather not admit. In addition to being the nation’s biggest provider of pay TV and Internet service, Comcast has built a network that is a huge part of the Internet backbone in the United States. This allows the company to wield great power.

Barry Tishgart, the vice president of Comcast Wholesale network services, spoke with Ars recently about Comcast’s infrastructure and its role in the peering and transit markets. He argued that Comcast’s opponents are distorting the facts when they say Netflix’s payment to Comcast was unprecedented and when they claim that Comcast shouldn’t receive such payments because it doesn’t operate a “global” network that connects to every part of the Internet.

It was “frustrating” that “people made the deal between Comcast and Netflix out to be unprecedented or new, that a content company—Netflix is an aggregation of a lot of content—would have a deal with a Comcast, but in fact that's been going on for a long time, and it's also been widely reported,” Tishgart said.

Netflix used to pay content delivery networks like Akamai to distribute its traffic. Companies like Akamai in turn pay ISPs for direct connections to the last-mile networks that serve home and business Internet customers.

Netflix eventually built its own content delivery network, asking ISPs to provide free connections or to take Netflix storage boxes inside their own networks to get video closer to customers. Some ISPs accepted Netflix’s traffic without payment, and Netflix boasts that it has interconnection agreements with 100 ISPs worldwide.

But Comcast and others such as Verizon and AT&T refused to provide interconnection for free.

Paying to relieve Internet congestion

Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and other content providers big enough to build out huge infrastructures already had direct connections to Comcast and other ISPs. Presumably, they pay for those connections, though payment details haven’t been made public.

“It's already known in the industry, Microsoft, Google, all the big guys are paying the ISPs,” analyst Dan Rayburn of Frost & Sullivan, an expert on the streaming media and interconnection industries, told Ars.

These paid peering connections give the Web giants un-congested links to the edge of each ISP network. This is not a “fast lane” in the usual sense of the phrase because the traffic isn’t accelerated beyond normal speeds after it enters the ISP network and starts to travel over the proverbial “last mile” to consumers. But the direct connections ensure the Web giants aren’t stuck in slow lanes before they reach last-mile networks. Shifting the largest sources of Web traffic into their own lanes can also relieve congestion on “middle-mile” networks that carry traffic for smaller Web companies who can’t afford their own direct connections.

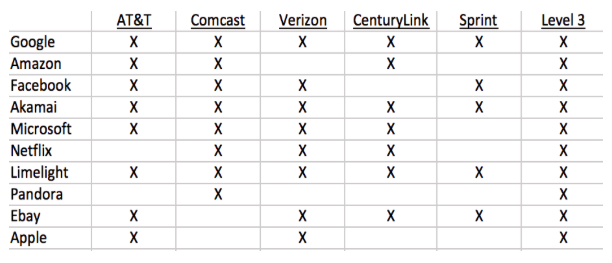

Publicly available routing data shows that Comcast has direct connections to Google, Amazon, Facebook, Akamai, Microsoft, Netflix, Limelight, and Pandora.

“You can see a lot of content networks that are directly connected to Comcast,” Tishgart said. “We have a peering policy, and many of those relationships have been in place for years before Netflix.”

Netflix has been able to avoid payments in many cases, securing free connections to the likes of Frontier, British Telecom, TDC, Clearwire, GVT, Telus, Bell Canada, Virgin, Cablevision, Google Fiber, Telmex, and RCN.

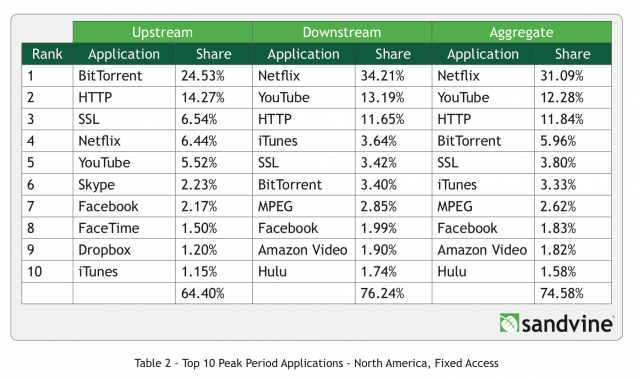

Google Fiber allows Netflix to peer for free even though Google is believed to be paying other ISPs for interconnection. While Google hasn’t raised a public fuss like Netflix has, it would benefit from free peering since it operates YouTube, the second largest streaming video service in North America after Netflix.

The Internet's middle-men

In cases when Netflix’s own CDN lacks direct connections to ISPs, the video company pays transit providers such as Level 3 or Cogent to send its traffic to last-mile ISPs. Level 3 and Cogent generally exchange traffic with the ISPs for free, but some of those ISPs balked when the addition of Netflix traffic forced them to upgrade connections. When Netflix accelerated the shift from third-party CDNs like Akamai to its own CDN in mid-2013, the links became saturated. Level 3 struck a deal with Comcast, the terms of which were undisclosed. Cogent refused to pay, and Comcast in turn refused to upgrade peering connections. Netflix videos began to stutter, and problems arose for other services that traveled over the same pipes.

Netflix and Comcast struck their paid peering deal in February, and the two quickly began joining their networks at peering points throughout the country. Congestion hit its peak in January 2014, but it remains a problem on networks such as AT&T that lack direct connections to Netflix.

Netflix is still angry that it had to pay Comcast (and Verizon), and the Federal Communications Commission is scrutinizing the deals. Comcast customers have good reason to be mad that Netflix performance suffered for months while the two companies argued over money, but at least performance has gotten better since the deal was struck.

Verizon customers aren’t so lucky. Even though Netflix agreed to pay Verizon for a direct path to its network, Verizon has been much slower than Comcast in rolling out the necessary infrastructure.

reader comments

317