The minds behind the streaming music subscription service Rdio have launched a companion video service named Vdio in the US as of Wednesday. While the two are related (maybe a little too related on the back-end, but we’ll get to that), they are hardly similar—Vdio requires individual purchases or rentals of content unlike Rdio, which lets users stream music based on their subscription price. Unfortunately, little about Vdio is compelling at launch, and it’s hard to envision it drawing users away from giants like Amazon Instant Video or iTunes in favor of Vdio’s prices, interface, or functionality.

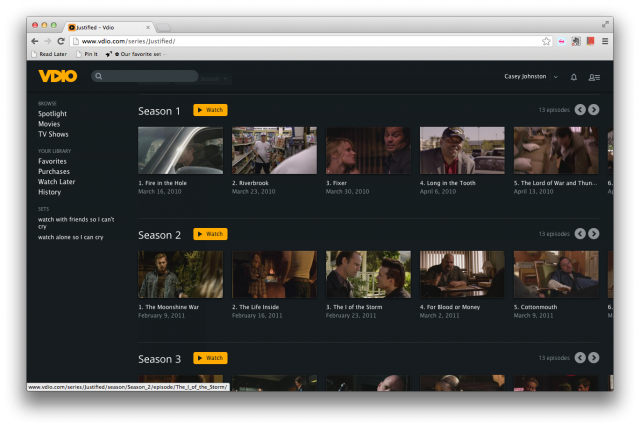

Currently, Vdio is only available to Rdio Unlimited subscribers who pay $9.99 each month for the music service. Those subscribers can now gain access to Vdio’s movies and TV shows, which are available for either rental or purchase. Movies are generally $4.99 to rent or $14.99 to buy, with older movies available at slightly cheaper prices ($3.99 to rent and $9.99 to buy, in the case of Dumb and Dumber). Both half-hour and hour-long episodes of TV are available for purchase at $2.99 each, or $29.99-$34.99 for a full season.

This doesn’t give Vdio a price advantage at all over similar services like iTunes or Amazon Instant Video. Both of these more established services offer cheaper content, especially in the case of shorter TV seasons or much older movies.

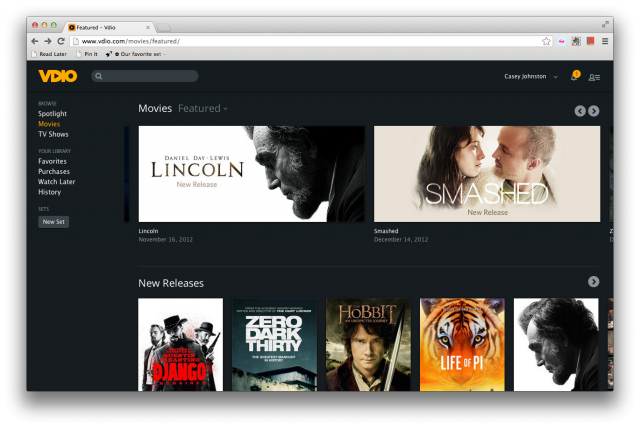

Vdio’s catalog can’t compare at all in breadth and depth to Amazon or iTunes, but what it lacks there it makes up for in timeliness and taste: as I browsed through the selections, there were relatively few shows that I didn’t either really enjoy or say to myself, “Oh yeah, I wanted to watch that.” As an example, the current movies that are front and center are part of the most recent Oscar crop: Lincoln, Django Unchained, and Zero Dark Thirty.

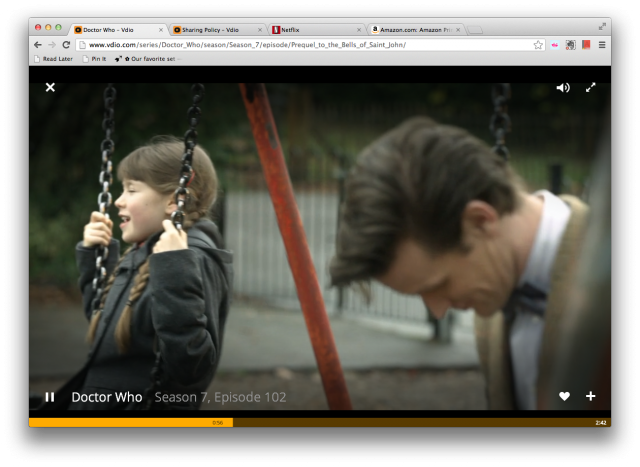

The playback interface is very minimalistic, and the videos appear to stream in HD. Unlike iTunes, there is no option to get a local digital copy of the video so you can view it offline, and there's no option to purchase in standard definition to save money. Amazon doesn’t allow file downloads to a computer either, but unlike with Vdio, users can download video content to either the Instant Video iOS or Android apps, as well as to Amazon’s Kindle Fire devices. Vdio’s lack of local options puts it behind its biggest competitors.

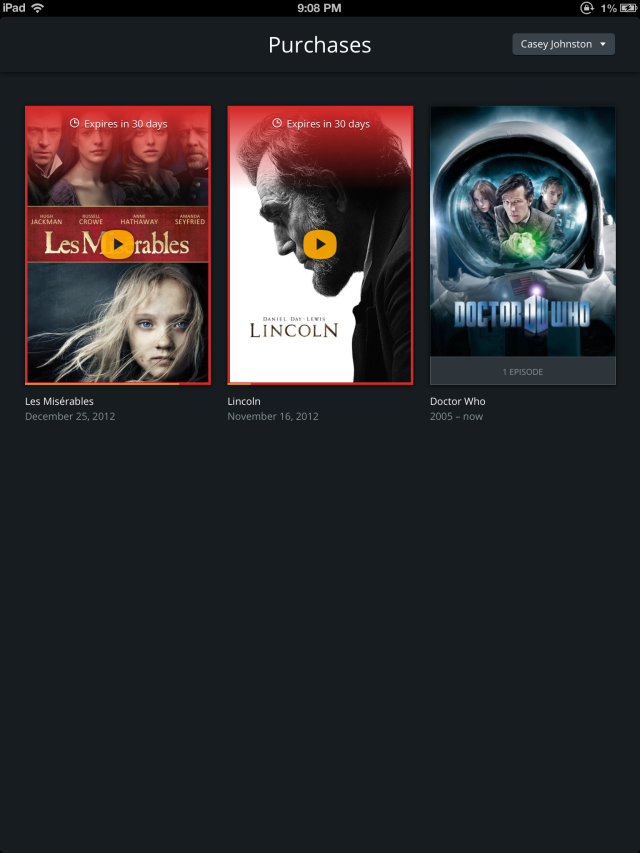

Vdio does have a companion iPad app, but it doesn't offer the option to make content local. It also does not offer the option to browse or purchase content; users can only watch items they’ve purchased through the Web interface. While there may be many reasons for this approach, mostly it seems to be a workaround to avoid paying a cut of in-app sales to Apple, per the company’s app policy.

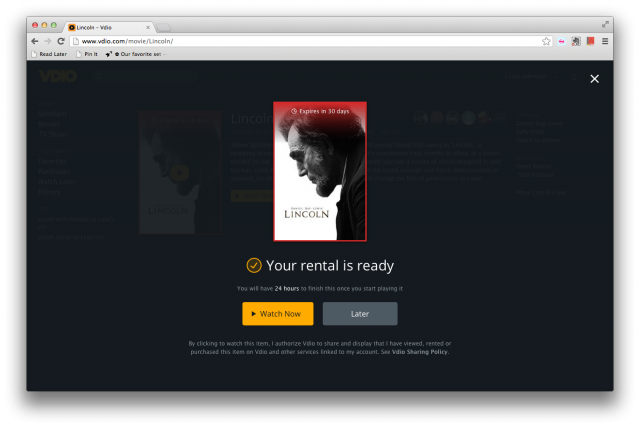

These quibbles may not be deal breakers for some users, but what we found most alarming about Vdio is its brazen privacy policy. When users select an item to rent or download, they are presented with a screen that states “By clicking to watch this item, I authorize Vdio to share and display that I have viewed, rented or purchased this item on Vdio and other services linked to my account.” A link to the Vdio sharing policy follows, which reads like an increasingly bad take-no-prisoners privacy nightmare.

It’s important to note that watching something on Vdio goes hand-in-hand with sharing that viewing on Vdio, and by extension, Rdio and any social media accounts you have connected to Rdio. Always. The second paragraph of the sharing policy reads:

When you consent to Vdio sharing your Viewing Activity, you are expressly permitting Vdio to share and/or publicly display such Viewing Activity on or through (i) the Vdio Service; (ii) the Rdio™ music service (“Rdio”), a service made available by an affiliate of Vdio; (iii) any third party social networking sites and services you have linked to your Vdio and/or Rdio accounts, such as Facebook or Twitter (“Social Networks”); and (iv) Vdio’s third party service providers, such as Vdio’s marketing service providers (collectively, the “Receiving Parties”). Accordingly, you expressly acknowledge that the Receiving Parties and anyone who may use their services will be able to freely view your Viewing Activity after you have provided your consent to share and/or publicly display such Viewing Activity.

Viewing activity that is freely viewable, forever. Yikes. And then the third paragraph continues:

In the future, Vdio may build additional privacy settings within the Vdio Service that will allow you to change the way in which your Viewing Activity is shared and/or displayed. In the meantime, if you want to stop sharing your Viewing Activity on or through Social Networks, you must unlink such sites and services from your Vdio and/or Rdio accounts through the Vdio and/or Rdio account settings. You will not be able to stop sharing your Viewing Activity on or through Rdio, as your Vdio and Rdio accounts will always be linked.

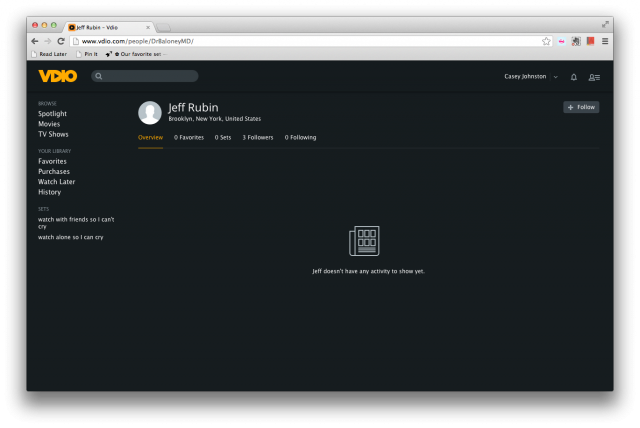

Maybe someday Vdio and Rdio will not be so inextricably linked; that is, you may not have to share everything you watch with the same people who see what you listen to. As it is, if you don’t want people on Facebook or Twitter to see what you watch, you have to unlink those accounts, and those people will no longer be able see the music you listen to, either. But as it stands, anyone who sees your listening habits and history on Rdio can always see everything you watch with Vdio.

The privacy policy further continues:

Once you have provided your consent with respect to a particular Viewing Activity, it cannot be revoked for that Viewing Activity (or any associated Viewing Activity), but you will have the option of not providing consent to share future Viewing Activity in each future instance.

Once you watch something (thereby also giving your consent that people can know about it) it can never be removed from your viewing history, ever. If you decide on a whim to watch Battleship, you’d better be prepared to defend that decision for eternity to any friends who have access to your Rdio profile.

This is not to say that Rdio doesn’t have some privacy settings; it's possible to have an account linked to Facebook without it pulling in your listening history. If you have a private Rdio account, you have to approve followers before they can view anything.

Still, the permanence and inability to separate Vdio activity from Rdio is a little unsettling. When Netflix added its (completely optional) social sharing service a couple of weeks ago, it included a button within the viewing interface for sharers to command the service to not share an item to friends. If Vdio is going to be so bold with its Rdio integration, it needs this type of granularity.

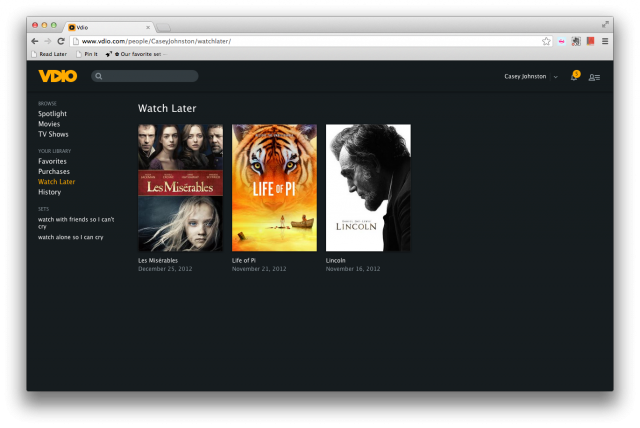

The purpose of Vdio's extensive sharing component is to aid discovery. Users are meant to be able to see what their friends watch, save videos to watch later, or curate selections into sets of movies to help them find new things and bond over mutual ones. In this pursuit, though, Vdio seems to reach too far.

Overall, unless you happen to be a diehard Rdio user, there is very little compelling you to spend your money here versus more developed services: the prices are not better, the service is not more comprehensive either in functionality or available content, and the privacy controls need some work. That’s not to say it can’t develop into something much more robust and competitive, but as it is, we can’t picture Rdio Unlimited users spending much money beyond the $25 credit they get when they activating Vdio before going dormant.

reader comments

29