Is Comcast really trying to wreck the open Internet with a set of new tollbooths? Is Level 3 really trying to browbeat its way to a good deal?

Ever since the Comcast/Level 3 interconnection dispute broke wide open into public view last week, the accusations from both sides have been flying. Sorting out those accusations has been difficult, in part because it was just so hard to know, on a technical level, what exactly has been going on.

Peering and transit issues can be notoriously complex but also murky, the details hidden behind nondisclosure agreements. As the 2009 Annual Report (PDF) from the ATLAS Internet Observatory put it, such deals are "difficult to quantify due to NDA/commercial privacy."

One upside of the dispute is that some of this secrecy has been lifted, and both sides have been unusually open with the press and with regulators about how they interact and what they believe to be at stake. If Level 3 is right, Comcast is trying to do nothing less than turn every Tier 1 network in the US into its customer, rather than the other way round. The result: a fundamental shift in network economics, and the beginning of an era in which the major ISPs start throwing their weight around, making it almost impossible for content companies to reach customers without paying each ISP an additional fee for direct network access. In this view, it's no coincidence that the big ISPs like Comcast, Verizon, and AT&T all operate content businesses of their own, including cable TV, video on demand, and IPTV.

If Comcast is right, Level 3 simply got in over its head and offered cut-rate pricing to Netflix in order to deliver the company's streaming video; now it needs to secure an unbelievable deal in order make the number work.

More fundamentally, the entire controversy is a reminder that there are no hard-and-fast rules about network interconnection; indeed, the increasingly complex nature of these interconnection deals means that it's not always clear, even to the participants, who should be paying whom. Traffic flows alone don't tell the story; it's all about perceived value. Now that "eyeball" networks like Comcast and "content" networks like Level 3 or Akamai have established deeply asymmetrical connections and traffic is often out of balance, should the content networks pay? As a 2008 paper from MIT and Akamai noted, "The question of who should pay whom to recover the costs of supporting that interconnection is ambiguous in this asymmetric world."

There's no better public example of that ambiguity than the Level 3/Comcast mudfight.

Some background

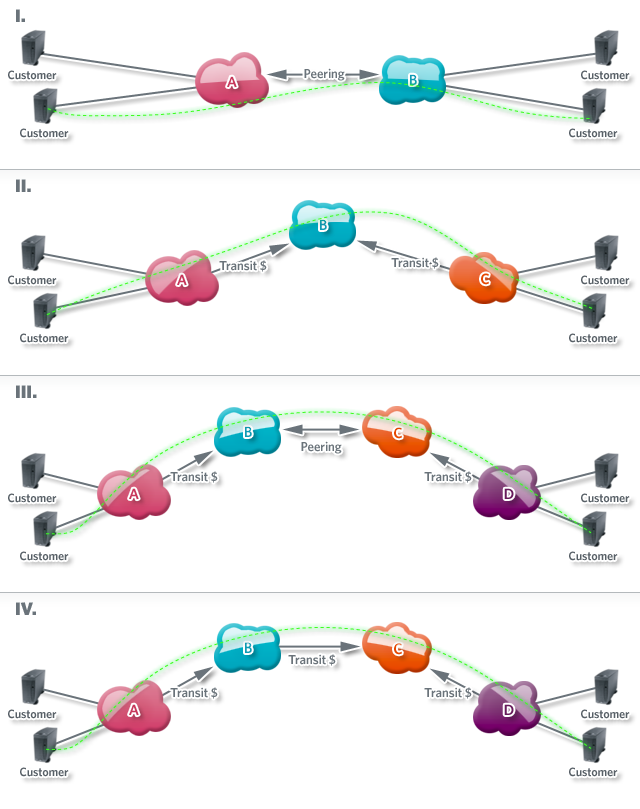

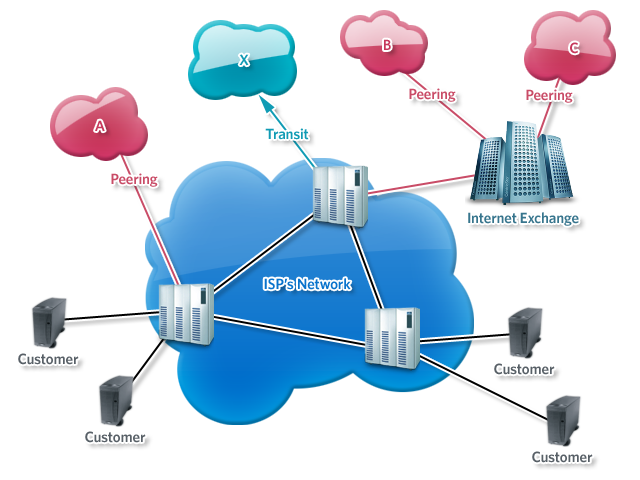

Prior to this dispute, Comcast and Level 3 had a longstanding, two-part relationship: they exchanged both free and paid traffic. Because Level 3 operates an Internet backbone, Comcast paid the company for true Internet "transit"—getting access to all the other networks with which Comcast had no direct interconnection. If a Comcast customer entered bbc.co.uk into her browser, for instance, that request could pass over Level 3's network and would be routed to the BBC's computers; traffic from the BBC could return on the same path. To make this work, Level 3 and Comcast had direct port-to-port network connections at various locations in the US.

But not all of the traffic passing across these connections was paid transit. Level 3 also operates a content delivery network (CDN) to provide cached (and therefore faster) access to streaming video and other content. If a Comcast customer tried to watch one of these videos, that request would then go to Level 3's network and would terminate there. The video that was returned would be handed to Comcast, and would be sent on to the user who requested it without leaving the network.

These two kinds of traffic ("on-net" and "off-net") were treated differently, even though they passed over the same interconnection points. Comcast paid Level 3 for off-net transit traffic, but Level 3 and Comcast exchanged on-net traffic without charging one another (called "settlement-free peering").

Who paid for the delivery of all this on-net traffic, then? The customers. In Level 3's case, this means that CDN customers like Netflix would pay Level 3, while Comcast's cable modem subscribers would pay Comcast. Very simple, very clean, and according to Level 3 now, this is the way the Internet should be connected.

But after winning the Netflix deal this autumn, Level 3 suddenly wanted to pass far more traffic over its links with Comcast. Comcast balked; Level 3 suddenly looked less like a transit vendor and more like a CDN. Comcast began talking about the imbalance in the two companies' traffic ratios and then demanded a fee from Level 3 for the traffic being dumped onto its network. (Indeed, Comcast's public peering policy states, "Applicant must maintain a traffic scale between its network and Comcast that enables a general balance of inbound versus outbound traffic.")

Comcast says that it didn't have the necessary 10 GigE ports available to meet's Level 3's demand, though it managed to dig up "customer" ports it could charge Level 3 to use. But Level 3 had never been a "customer" of Comcast before; the relationship had always been the other way round. Now, Comcast claimed that, due the traffic imbalance between the two, Level 3 had to become both a transit vendor and a paid peering customer.

Level 3 objected, arguing that it wasn't increasing Comcast's costs with the extra traffic. The company tells me that it actually offered to give the necessary hardware to Comcast (at around $50,000 per port) and that it offered to do "cold-potato" routing deep into Comcast's network, dropping off streaming traffic near the customers who requested it, for instance. This would save Comcast money, since the cable giant wouldn't have to sling this streaming traffic across the country on its own network. Comcast said that wasn't good enough; it wanted cash.

Level 3 felt trapped. It could "just take it" or it could "take it and complain," the company's legal counsel John Ryan told me. It chose the latter.

"It's not about the money that we're now being forced to pay Comcast," he added. It's about the precedent.. and what it might have to pay in the future.

reader comments

147